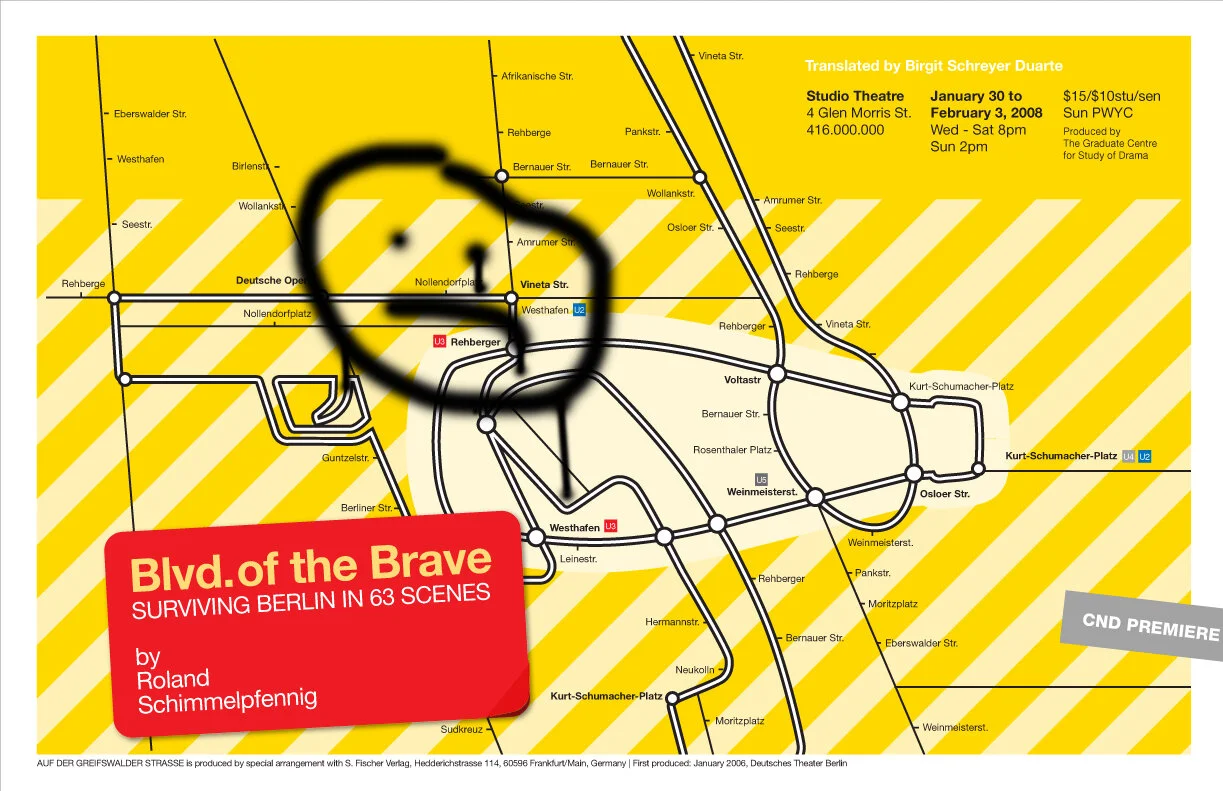

BOULEVARD OF THE BRAVE

(AUF DER GREIFSWALDER STRASSE)

By Roland Schimmelpfennig

translated and directed by Birgit Schreyer Duarte

Studio Theatre, University of Toronto

Jan 30 – Feb 3, 2008

ENGLISH LANGUAGE PREMIERE

CAST

Man without Dog / Hans / Romanian Man 3 / Owner of the pub Katsky Keith Bennie. Woman with Green eyes / Second Woman with Green eyes /Teubchen Jennifer Heywood-Jackson. Rudolf Guillermo Verdecchia. Rocker with plastic bag / Streetcar track worker 2 / Construction worker 2 / Romanian Man 2 / Fritz Mark Purvis. Terribly Thin Woman / Girl in the streetcar / Schmidti Tory Mountain. Katja Julia Hune Brown. Simona Lydia Wilkinson. Maika Christine Armstrong. Bille Jordana Commisso. Kiki, Rudolf’s girlfriend / Hans’ Wife / Wife of Man without Dog Charlotte Powell. Man on the Phone / Streetcar track worker 1 / Romanian Man 1 / Man with Horse carriage Tyler Seguin.

CREATIVE TEAM

Set & Costumes Becky Bridger and Elizabeth Cameron. Lighting Aaron Bieman and Michelle MacArthur. Assistant Director & Production Dramaturg Natalie McCallum. Research Dramaturgs Anam Ahmed, Amy Mayor. Sound Designer Steph Berntson. Stage Management Laurel Green, Jessica Cimo (ASM), Emily Hincks (ASM). Production Manager Marie Dame. Costume Assistant Tara Egan Wu. Props Supervisor Carolyn Farrell. Video Technician Mikaela Dyke. Producer Graduate Centre for Study of Drama, Theatre and Performance, University of Toronto. Poster Design and Set Graphics Louis Schreyer Duarte.

Graphic Design by Louis Schreyer Duarte

ABOUT THE PLAY

In the course of 24 hours, the lives of 37 people who live, work, visit and die on a low-income street in Berlin’s North-East intersect in seemingly banal and accidental ways. Through Roland Schimmelpfennig’s own signature dramaturgy of laconic, hyper-realistic snap shots, magic realism, fairy tale and prose narrative he leads the spectator’s gaze back and forth between the two sides of a loud and busy street—from one human fate to the next, spanning generations bound together by this neighborhood of the forgotten.

As Eva Behrendt of Theater Heute writes about Germany’s most prolific contemporary dramatist, his works “unfold ... a compelling and virtuosic social panorama of our time. Seemingly fragmentarily assembled stories that break off abruptly come together … to form a kind of painting which both painfully and humorously compresses the improbable and mysterious aspects of life, the everyday and the banal, the unpredictable, fortune and misfortune, to make an interwoven network of relationships provide each other with impulses, like billiard balls knocking together, so as to discover fresh constellations.”

DIRECTOR’S NOTES

I am excited to be presenting the first German translation of Roland Schimmelpfennig’s 2006 play, with the original title Auf der Greifswalder Strasse. Prenzlauer Berg with its Greifswalder Street, the Berlin neighborhood after which Schimmelpfennig named his play, is in a lot of ways the “Queen West West” area of Berlin. A recent article in Die Zeit reveals that real-estate buyers in this newly hip, bohemian district “want a hint of big city thrill, without having to look down on too much misery”—that’s why penthouses and lofts are the hottest commodity of the neighborhood these days. As a result of the past decade’s rapid gentrification, only the extremes of society remain here: the “victims of reunification who were too weak even to leave the borough, and the newcomers with their victor mentality who tend to have little sympathy. Here 1989 [the reunification of East and West Germany] was a short sharp shock followed by a spell of almost complete freedom, and now all that is left is rich and poor.” And nothing is what it seems: even among the high end of the income gap, there is “a certain degree of loneliness” in the district—psychotherapists are booked up.

While the stark contrasts of this neighborhood certainly inspired his play, Schimmelpfennig knows that in theatre any direct translation of reality to the stage is impossible, not even desirable. On the contrary—he claims:

“I like it when the theatre lays its cards on the table. Perhaps we have to enforce simplicity through complexity.”

For me, the process of translating and directing Boulevard of the Brave revealed of course much more than just how translation decisions influence performance and vice versa. Just as in the world of the play transformations become possible and the usual borders and viewpoints start to shift, they also shifted for us. Translating this play with the vague prospect of staging my own production of it was certainly a leap of faith for me, and I’d like to thank the Drama Centre’s theatres committee for their faith in the project. First, the text presented itself as strangely inaccessible and enticing at the same time. Fantastic imagery clashes with the overtly mundane. Stage directions obsessed with detail contrast with the dialogue’s lack of contextualization. Emotional outbursts of some characters alternate with a chilly psychological ambiguity of tone in others. What I ultimately found is that the text invites you to use it as raw material, despite its concrete setting and extreme detailed descriptions of location: its hybrid genre of fairy tale, societal study, comedy, tragedy and magical realism, as well as its fragmentation in structure allowed us to play up what spoke to us, and to “fill in the blanks” accordingly—according to our ideas of what theatre can and should do, and according to our ideas of cultural specificity.

We started off with the best intentions to treat the play’s very concrete, specific location, Greifswalder Street, as a mere metaphor, a starting point to explore themes like transformation and transgression of boundaries, inevitability, isolation, geography of family and history, and the question to what extent we as humans are mere subjects of our circumstances. And yet, the more we attempted to stay away from grounding the production in a Berlin setting, the more we found ourselves drawn back to the splashes of cultural distinction we felt the original environment of this play evokes. Frankfurters without buns instead of hot dogs for the construction workers; “Schlager” music for the elderly dog owners; German tabloids for the cashiers; fragments of the old divide of the city with its multiple layers of history in set and projection design. Does this mean that it is, after all, exploring specificity what allows us to gain insight into the general condition of humanity? Too far-fetched, too risky of a conclusion we might think…and yet, the world of the play seeks to show us the possibilities that open up when we allow ourselves to recognize the familiar within the foreign and the marvelous behind the mundane. I believe the translated version of the text will explore these tensions in its own terms by offering access to an English-speaking, thus “unfamiliar” audience. Let us embrace the inexplicable and believe in the improbable.

What was most appealing about Boulevard was the little bubble of

reality it created for itself, that was located neither in Berlin nor

on a stage in Toronto. If it was foreign, it was not that it was set

in Germany, but that it had descended from Someplace Else - that place

where people speak a little funny and curious things happen at night-

and was still populated by moments of surprising tenderness.

I.T., audience member